- Our School

- Admissions

-

Academics

- Divisions and Faculty

- Commencement 2024

- January Term

- International Program (ESOL)

- College and Career Counseling

- Upward Bound

- Library/Monahan Academic Commons

- Career/Technical Education

- Lyndon Learning Collaborative

- Flexible Lyndon Institute Pathways (FLIP)

- Specialized Instruction

- Adult Continuing Education

- Lyndon Institute Course Catalog

- Student Services

- Arts

- Athletics

- Campus Life

- Support LI

- Alumni

« Back

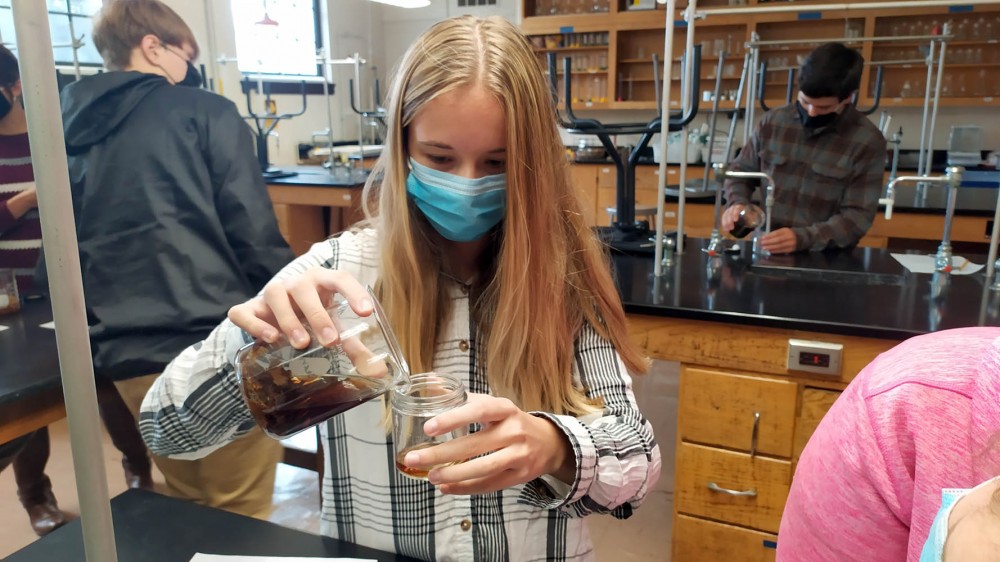

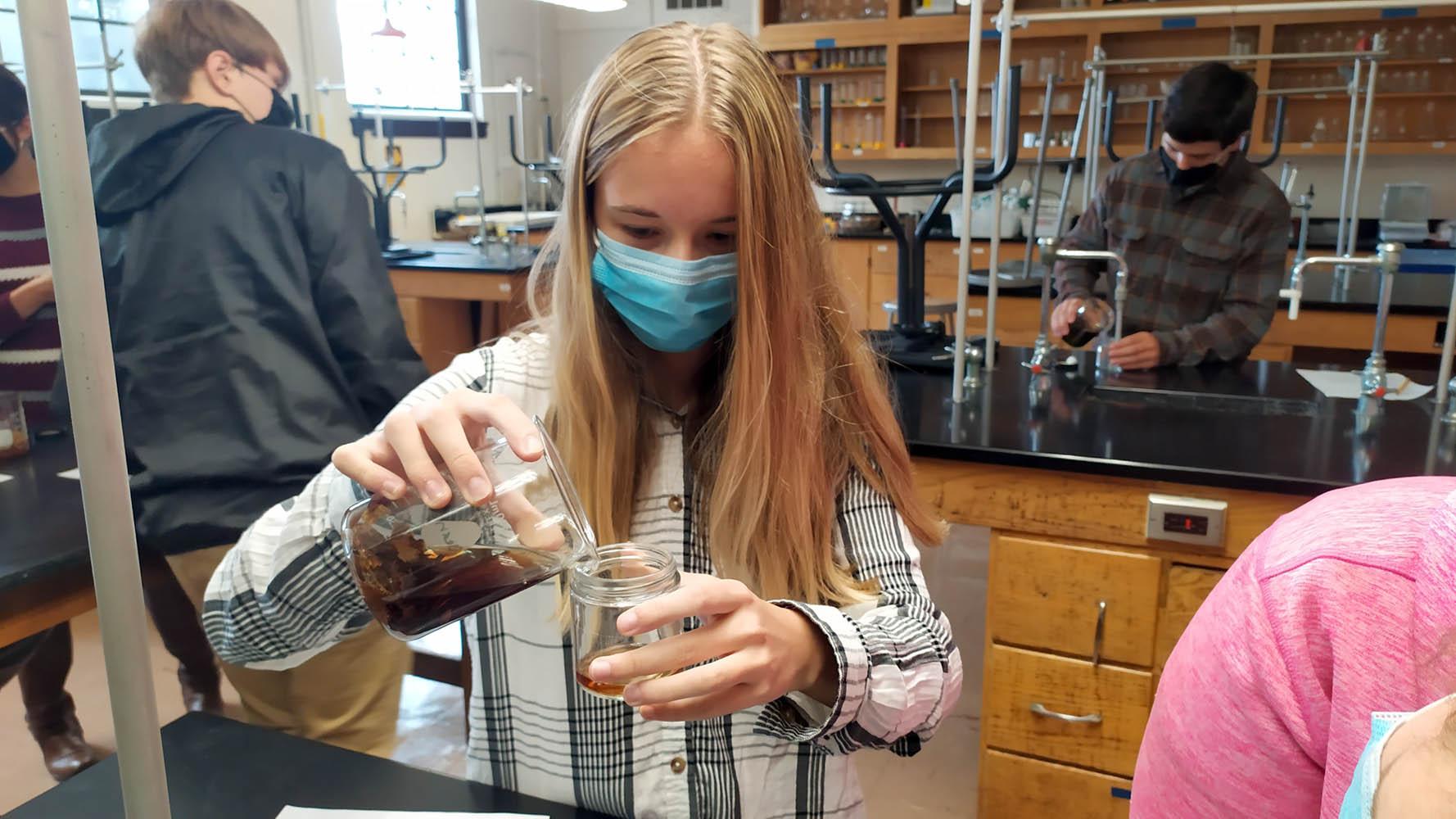

Class Acts: A Leaf by Any Other Color

October 16th, 2020

By: David Stahler Jr.

Fall sets fire to the trees, turning green to red, orange, and gold. For a few short weeks, our Vermont landscape is transformed, nature’s last treat before we begin to brace ourselves for the imminent darkness and snow. We wander the woods, take pictures of hills ablaze, and jump into piles of color. The season is always a surprise—the timing, the duration, the intensity, the dominant shades (this year’s reds were particularly spectacular in the NEK)—with no two years ever quite the same.

This autumn, Lyndon Institute science teachers Rachel Riendeau and Lauren Ruffner gave their biology students an opportunity to appreciate the season on a whole new level by turning the outdoors into a laboratory and introducing them to the world of chromatography.

Students learned the science behind plant pigmentation and what happens when the dominant green chlorophyll of life-giving photosynthesis breaks down, allowing a leaf’s other pigments—the carotenoids (yellow and orange) and anthocyanins (red)—to emerge.

The first step of the experiment is the fun part—a journey back to childhood, as the students head outside to gather leaves from the campus’s maples, beeches, birches, and oaks, samples of every shade they can find, from the deepest red to the brightest gold, along with a few leaves still clinging to their green. From there, the leaves make their own journey to the lab where they are separated by color and broken down in a solution of isopropyl alcohol. Before long, the alcohol has absorbed each leaf’s pigments, going from clear to colorful, the line of beakers forming a spectrum across the lab bench.

With the pigments extracted, a small amount of the mixture is transferred to a new beaker, one for each different color, and a strip of chromatography paper is suspended into the solution, dipping just below the surface. Slowly, the paper absorbs the solution, transforming from creamy white to a tinted strip of variegated color showing all the different permutations of the leaf’s dominant pigments, nature's own watercolor painting.

“We live in the perfect area to explore this topic,” Ruffner told me. “I start by asking my students, ‘Why do leaves change color?’ Their initial response is, ‘Because that’s just what they do!’ But once they learn the science behind how the trees prepare themselves for winter, they’re surprised to discover what’s happening on a chemical level.”

They’re especially surprised to learn that these beautiful fall colors have been living within the leaf’s genetics all along, that it’s only when the dominating green chlorophyll of spring and summer breaks down with the onset of growing darkness and increasing cold that the hidden brilliance is allowed to emerge. In adversity, their full potential is revealed. For a young person in 2020, it’s a powerful and important lesson to absorb.

Photo caption: Lyndon Institute sophomore Natalie Webster pours off a liquid solution created from fall tree leaves broken down in isopropyl alcohol into a secondary beaker as part of a chromatography project.

Photo caption: Beakers containing fall leaves soaking in a solution of isopropyl alcohol line a table in a Lyndon Institute science lab as part of a chromatography project.

Posted in the category Front Page.